Between December 2012 and May 2013, Time magazine went from declaring “selfie” one of the Top 10 Buzzwords of the year to lambasting “The Me Me Me Generation” on their front cover. Since then, the battlefield designated by these two poles has been tread flat with skirmishes. Selfie apologists weaponize the language of empowerment and entrepreneurship while detractors raise concerns over inauthenticity and surveillance. What seems to be the crux of both arguments is power: are we are setting the terms for our presentations, or are we simply arming a malicious ether with our likenesses?

The black mirror, or Claude glass, is similarly a tool of power. In its facade, all of nature is distilled and composed for the artist’s gaze. However, consider: who held these mirrors? In the 18th and 19th centuries, who could walk freely through a picturesque landscape? Who had the time and means to decide to paint it? Who was allowed the distance necessary to observe? Now, as we speak of a generation enraptured by our reflections, can we say the glass has passed hands?

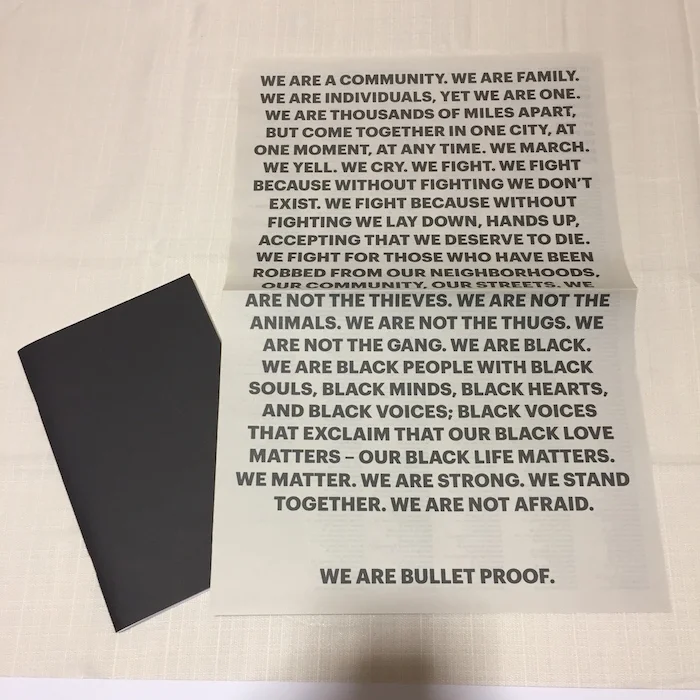

As cultural conversations turn to the proliferation of self, the question of whether art should ‘hide the artist’ should not be removed from the question of power. Some artists simply cannot hide. For so long as the black mirror is held by the institution, the marginalized artist remains the subject on view. In the glass, her reflection is diffused—not the sharp specificity of the individual but the simplification of a (skin) tonal range. As Hannah Black writes, “the identity artist has to exemplify a race/gender category, but as soon as she steps into the institution’s embrace, she becomes an example of universality.” What does it mean that entire artistic designations are delineated by the artists’ categorical identities rather than the content, the medium, the form of the works?

The artist of color (and all its intersections), is familiar with this conflation. There is never an individual; it is always “all of us.” If the artist hides, it is less her decision and more an erasure, a disavowal. For a subject on view, all of choice swings on the fulcrum of identity, and there is no escape from the omnipresent eye.

Martine Gutierrez: “Hands Up”

Interested in the fluidity of relationships and the role of genders within them, Martine Gutierrez offers mannequins in her own stead to explore the diverse narratives of intimacy. Life-size props blur into a discourse about what it means to be ‘genuine,’ where interpretations of dichotomous constructs such as ‘gay’ vs ‘straight,’ or ‘reality’ vs ‘fantasy’ are revealed as subjective and mutable. Acting as a conduit, Martine supplies a framework that facilitates a dialogue requiring the viewer to question their own perceptions of sex, gender, and social groups.

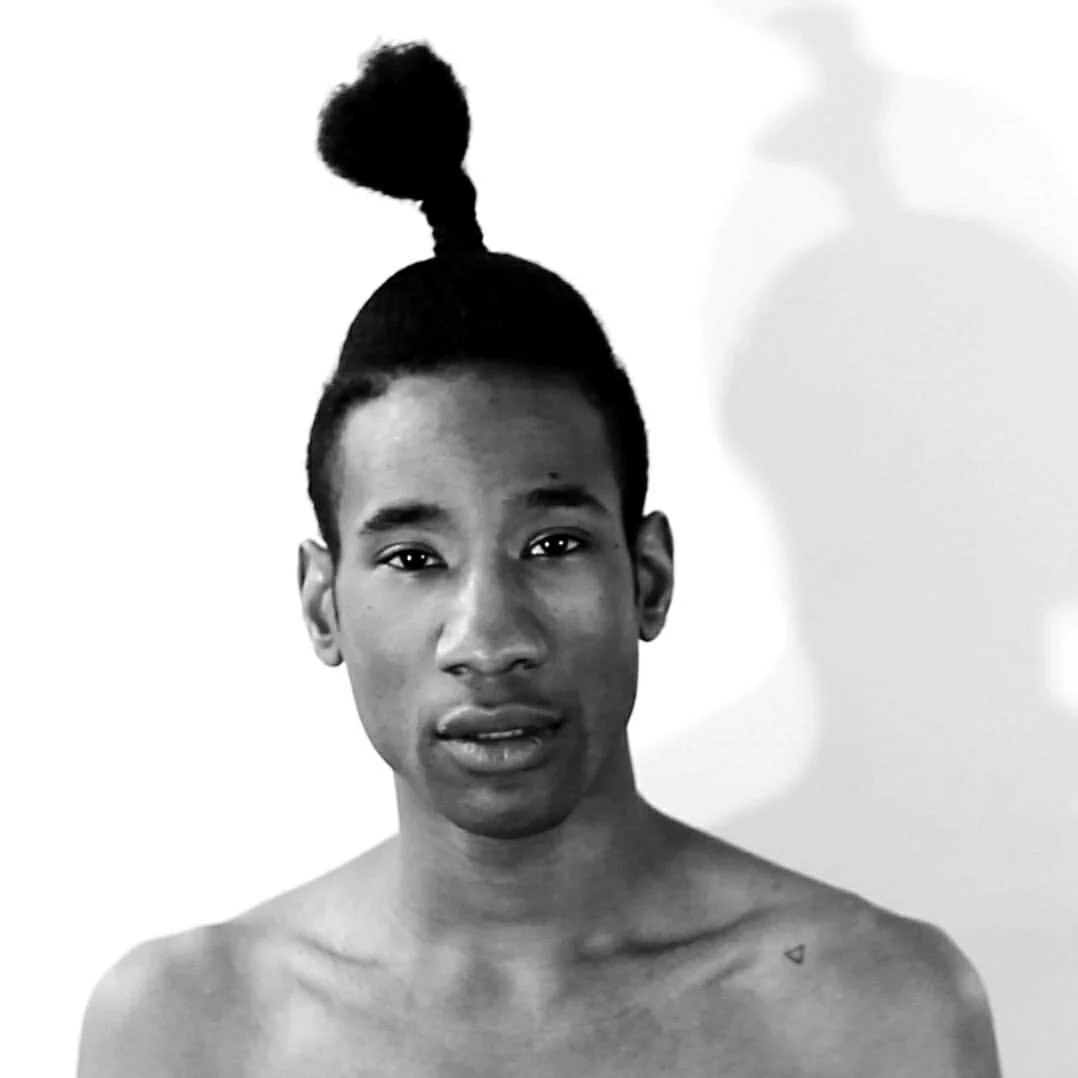

Jarrett Key: “Hair Painting No. 11” and “Hair Painting No. 14”

Jarrett Key’s Hair Paintings are as personal as they are political, and political because they are personal. Scored with an oral history of Jarrett’s late grandmother, these choreographed performances recount their family’s specific rituals through the use of their black hair—an intensely charged symbol of respectability politics, workplace discrimination, and beauty standards—as the mark-making tool. Though the resulting paintings can exist within a European abstract art historical context, Jarrett’s black body on view carries the weight of their difference, serving to ingratiate or alienate the audience in turn with their history, personhood, pathos, and joy.

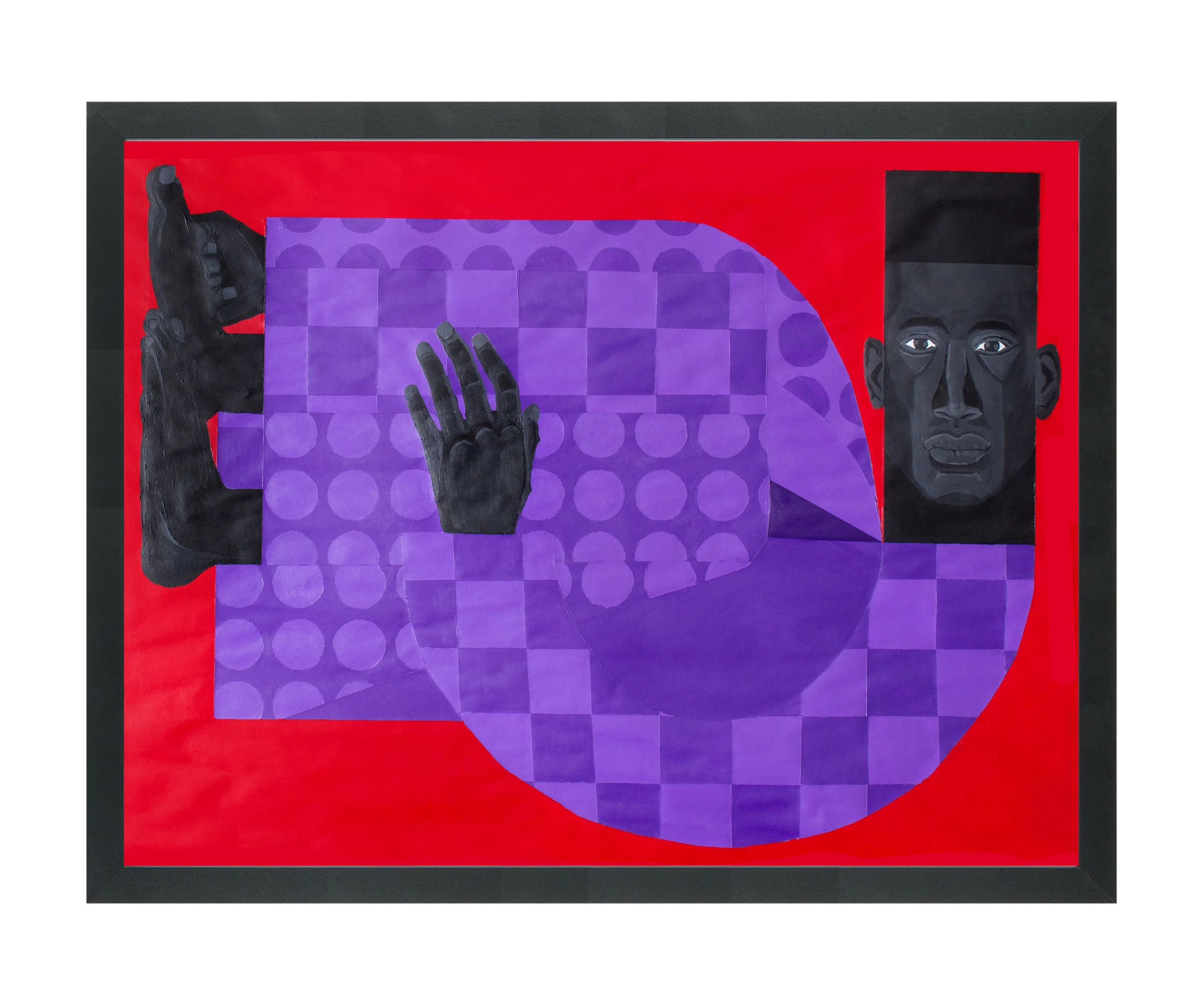

Jon Key: “Man in the Violet Suit No. 2(Green)” and “Man in the Violet Suit No. 3 (Red)”

As abstractions of the Queer Black Man, a category whose members already walk society as caricatures, Jon Key's “Man in the Violet Suit” series plays on the assumption of self-portraiture. The subject of the paintings is simultaneously flamboyant and flattened, provocative and subdued. The frame stifles, but the eyes accuse elsewhere. The collaged elements are also painted, claiming the verisimilitude of photography in role but embodying the ambiguity of pictorialization in form; the Man, who may or may not be the artist, explores how distance from perception cannot fully negate the gradation between the viewer and the self.

Yves-Olivier Mandereau: “Porncelain”

Yves-Olivier Mandereau’s “Porncelain” reappropriates fine china as a means of confrontation between ‘The Christian Home’ and his homosexuality, staged on the most hallowed locus of the family hearth—the dinner table. Yves-Olivier subverts the heirloom, a beacon of traditional values, with gay pornography, a personal utopia in which he had found himself unafraid. “Porncelain” is both cheeky and traumatic, a preemptive strike at ‘The Conversation’ that also raises questions of a legacy for the queer community, which stands as the only classified social grouping without any generational inheritance of material culture.

Emily Oliveira: "Labor-In-Vain"

With “Labor-In-Vain,” Emily Oliveira draws a thread between the domestic labor of women’s crafts, the invisible and outsourced labor of black and brown women textile workers, and the physical labor of women body builders. Their utility interrupted by the assemblage materials, the embroidered pillows reject the notion of the handmade as a relic of the past and instead place themselves in the visceral present of global labor, economic disparity, and food security. “Labor-in-Vain” examines the ways in which feminized labor is marginalized—both when it aligns with the desires of men and market, and when it directly subverts those desires.

The artists in STANDARD STANDARD are not monolith but acknowledge the possibility of being viewed as such. Their work confronts, accepts, or simply exists in their responsibility as it relates to their truths. They fly their own standards, aware to which they will be held.

For more information, please visit springbreakartshow.com or contact kat.jk.lee [at] gmail [dot] com.